The Hospitality Project

What is The Hospitality Project?

As a way of affirming the irrepressible solidarities joining youth to youth, I am inviting students (and those who were once students) to write letters of welcome and encouragement to Mr. Omar Khadr.

These letters can be brief or long and about any topic, but written in the spirit of hospitality and in the name of peaceableness and humane reconciliation. It’s up to you to decide: a friendly greeting; a wish for good health and prosperity; an expression of solidarity; a reflection upon war; a desire for peace; a longing for understanding; an entreaty; a salut; an apology; a gesture of regret; an invitation to share a meal and good conversation.

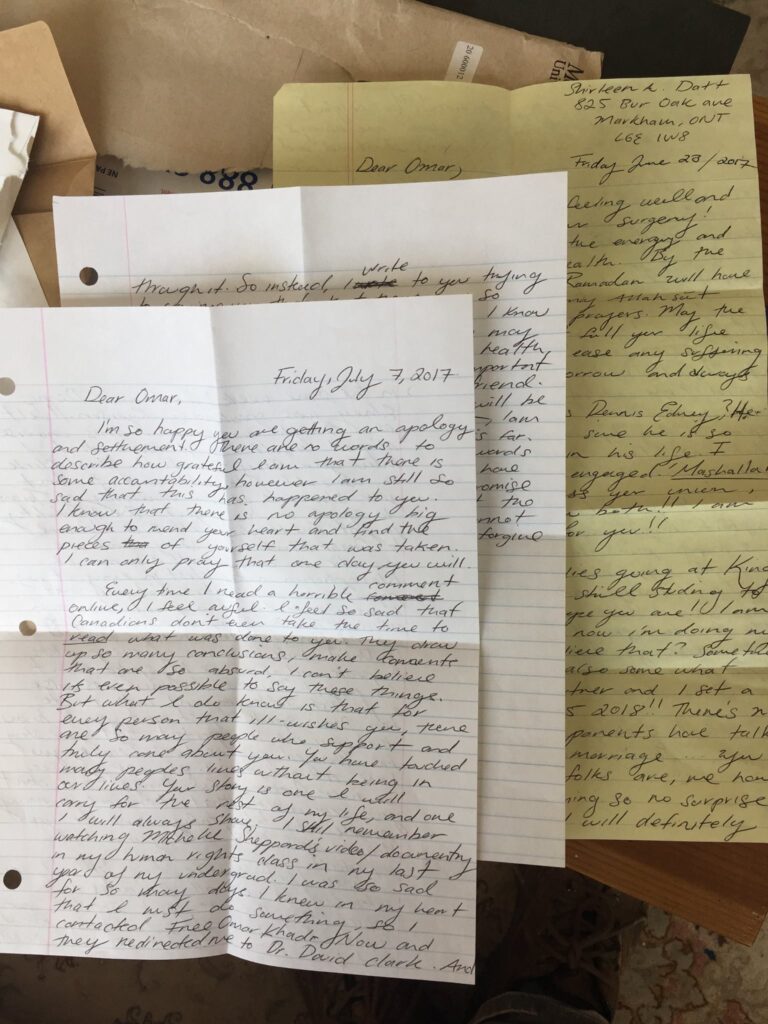

Many students have written letters for The Hospitality Project. A broad selection of those letters is posted here for your consideration and, hopefully, inspiration. Most students send word-processed letters, but a few have elected to personalize them by writing them out in hand or sending them in the form of post-cards.

My hope is that students and those who were once students will continue to take up this challenge, demonstrating by example the importance of fostering shared understandings rather than individual fears.

How Did The Hospitality Project Begin?

In 2015, I wrote a public letter to the President and Vice-Chancellor of McMaster University, where I teach, suggesting that we hold a spot open for Khadr in our first-year undergraduate class, should he be interested in attending and in a position to do so. I offered to provide Khadr any remedial education that he might need to qualify for entrance into a first-year English course and concluded by saying that an intellectually verdant place like McMaster University would not only have a great deal to offer Khadr, whose life and whose education had otherwise been subject to such sustained degradation, but also that Khadr would undoubtedly have very much to bring to us. In the back of my mind was the United Nations convention, to which Canada is a leading signatory, that calls for the rehabilitative education of child solders, not their vilification, torture, criminalization and imprisonment. Only later did I learn that at almost exactly the same time as I made my appeal to McMaster’s President, one of Khadr’s lawyers had petitioned Dr. Melanie Humphreys, the President of The King’s University, a private Christian university in Edmonton, to offer Khadr a seat in its first-year class.

McMaster University turned down my request. But the public letter prompted lots of interest not only in the media but also, more important, among students, who overwhelmingly supported my endeavour. The Hospitality Project acknowledges the welcoming spirit of those students and seeks to give them a public venue in which to make peace and to practice hospitality.

The Letters

Many students have written letters for The Hospitality Project. A broad selection of those letters is posted here for your consideration and, hopefully, inspiration.Most students send word-processed letters, but a few have elected to personalize them by writing them out in hand or sending them in the form of post-cards.

Letters should be addressed to Mr. Khadr, care of 500goodwishes@gmail.com. Your return address will be removed. You do not need to sign your letter. It is writing the letter of welcome that counts whether you feel able to attach your name or not! All letters will be posted on The Hospitality Project website. When we reach five hundred letters, I will have them printed and delivered to Mr. Khadr.

These letters serve many different functions:

- They greet and affirm a Canadian citizen and former child soldier who was tortured during his more than decade long extra-legal incarceration in Guantanamo Bay.

- They form an occasion to reflect upon the complicity of Canadians in Khadr’s treatment, which violated international law, the United Nations Convention on Rights of a Child, and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

- They reject the punitive and Islamophobic demonization of Mr. Khadr as “a murderous terrorist.”

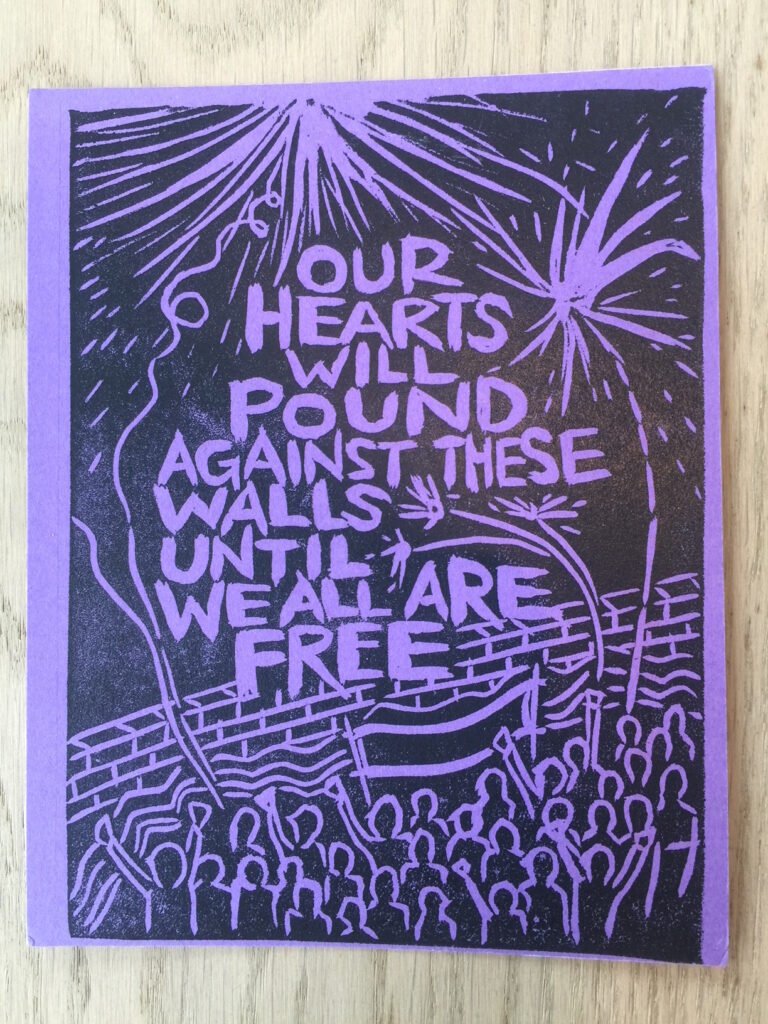

- They constitute a practice of peace during a vexed time of militarization and war, including the war against youth and the war against thought.

- They confirm the important relationship between higher education, critical citizenship, and the practice of social justice.

Who is Omar Khadr?

Shuttled between Pakistan and his home in Toronto as a boy, Khadr was eventually left in the custody of guerrilla fighters outside Khost, in eastern Afghanistan, where, his father believed, his knowledge of English and Pashto could serve a purpose. That was in the summer of 2002, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Taliban regime and while the country was still under a ferocious assault by U.S. and Coalition forces in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. Afghanistan was an extremely dangerous place to be, but Ahmed Said Khadr, who had close ties to Al-Qaeda and who would later die in a battle with Pakistani security forces, left his youngest son in harm’s way. Khadr was then but fifteen years of age. On 27 July he was severely wounded in the midst of a firefight with American military forces that bombed and strafed the safe house in which he and a group of guerrillas had been discovered. That battle left Sergeant Christopher J. Speer with a severe head wound to which he succumbed two weeks later. All of the insurgents were killed. Khadr was blamed for throwing the grenade that led to Sergeant Speer’s death, although no eye-witness evidence supports that claim. Under torture, Khadr confessed to the crime, assuming what happened under these wartime conditions is classifiable as a crime, but later said that he had no recollection of the event. Sworn testimony that was accidentally released by the U.S. military in 2008 confirms that Khadr could not have been responsible for the American soldier’s death, not least because of the grievous nature of his own wounds. Blinded in one eye and injured in the other, his body riven with shrapnel wounds, Khadr was shot twice in the back by American soldiers as they overran the compound. Before falling unconscious, the teenager begged to be killed. But because he made this plea in English, automatically making him an intelligence asset, his life was spared. Khadr was transported to Bagram Air Force base, where he was tortured and interrogated by guards who singled him out “for the worst treatment, payback for allegedly killing one of their own” (Michelle Shephard Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, 90). From Bagram he was taken to the notorious prison complex at Guantanamo Bay. During his lengthy incarceration there, Khadr was denied proper medical treatment for his wounds (including injuries for which he is only now, thirteen years later, being treated in Canada and was subjected to various forms of torture, including sleep deprivation, physical abuse, threats of rape, and significant stretches of solitary confinement. He was repeatedly shackled in stress positions to concrete floors, and sometimes forced to use his body to wipe up his own urine. In flagrant violation of Canadian law, Canadian intelligence officials interrogated him knowing that he had been tortured with the specific intent of making him more pliable. Khadr did not speak to a lawyer for almost two years after his transportation to Guantanamo and it would be another year after that before he was charged with war crimes (Human Rights Watch). He was the prison’s youngest detainee. All other countries in the world repatriated their prisoners from Guantanamo. But seeking to appease the Bush administration, and cynically believing that abandoning a vilified Muslim to indefinite detention could only garner political support at home, the Canadian government forsook the teenager. In 2004, the U.S. Military Commission deemed Khadr to be an “unlawful enemy combatant” – meaning that the Geneva Conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners and the United Nations protocols regarding the rights of the child did not apply. Instead, Khadr was forced to endure living in a brutal state of exception with no due process, no right of appeal, no right to a trial, and where evidence gathered by torture was fully admissible. For a quarter of his young life, he suffered at the hands of a carceral system so repugnantly at odds with the principles of justice that the U.S. declared it illegal for any of its own citizens to be subject to its punishing force. As Michael Keefer eloquently puts it:

Omar Khadr has been the victim of a triple suspension of what ought to have been his by right—as a child, a citizen, and a human being. His father’s political fanaticism led to a suspension of the parental protection that is the normal anchorage of a child’s world, exposing him at age fifteen to the military power of an imperial state that had cast off the constraints of those international laws which define the basic rights accruing to us as human beings—and exposing him, as well, to the betrayal of his rights as a citizen by a Canadian government that, first through cowardice and then through harsh conviction, shaped its own notions of legality to the prevailing wind. (“The Triple Victimization of Omar Khadr.” ColdType 98 [Mid-May 2015]: 28-31.)

When Dennis Edney, the Canadian lawyer who eventually took on Khadr’s case, and who has continued to be his tireless advocate, first met him in 2005, he described the teenager as a “broken bird,” a mute and crushed boy who for years had lived with “no education, no psychological assessment, and no Canadian consular representation” (quoted in Keefer 30). Khadr’s inhumane and illegal treatment is now a matter of public record, the full description of which formed part of Edney’s submissions to various courts, including the Supreme Court of Canada, which three times found that his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms had been violated. When his case finally came to trial before the US Military Commission, it was the first war crimes trial in history for a minor. The unseemly spectacle of trying a child captured on a battlefield may have been the most important reason for the U.S. Military Commission’s decision to accept a plea-bargain and to allow Khadr to be delivered into Canadian custody a decade after his capture. In 2010 Khadr plead guilty to war crimes and transferred to Canada, where he was expected to serve the remainder of his sentence in a maximum security prison. Once in Canada, Khadr’s lawyer applied for bail for his client. Over the vigorous objections of the federal government, which continued to characterize the young man as a security threat, an Alberta judge granted him that constitutional right in April 2015. In July 2017 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government agreed to a $10.5 million settlement with Khadr.

To see Omar Khadr and to hear him speak in his own words, see a brief 2015 news conference held when he was released on bail:

Further Reading

For a selection of articles and interviews regarding Omar Khadr and The Hospitality Project see:

- Can the University Stand for Peace?

- The Canadian University and the War Against Omar Khadr

- What Does it Mean to Welcome Omar Khadr?

- Letter by Letter

- Universities Have a Voice

Tyler Pollard interviews David L. Clark. “The Canadian University and the War Against Omar Khadr,” Public Intellectuals Project, 17 May 2015.

Tyler Pollard interviews David L. Clark, “What does it mean to welcome Omar Khadr? University students and the lesson of hospitality,” Public Intellectuals Project, 19 September 2015.

Sophia Topper, “Letter by letter: McMaster professor who opened seat for Omar Khadr launches new initiative to promote friendship and hospitality,” The Silhouette, 17 September 2015.

The Queen’s University Journal, “Universities have a voice,” The Queen’s University Journal, 2 June 2015.